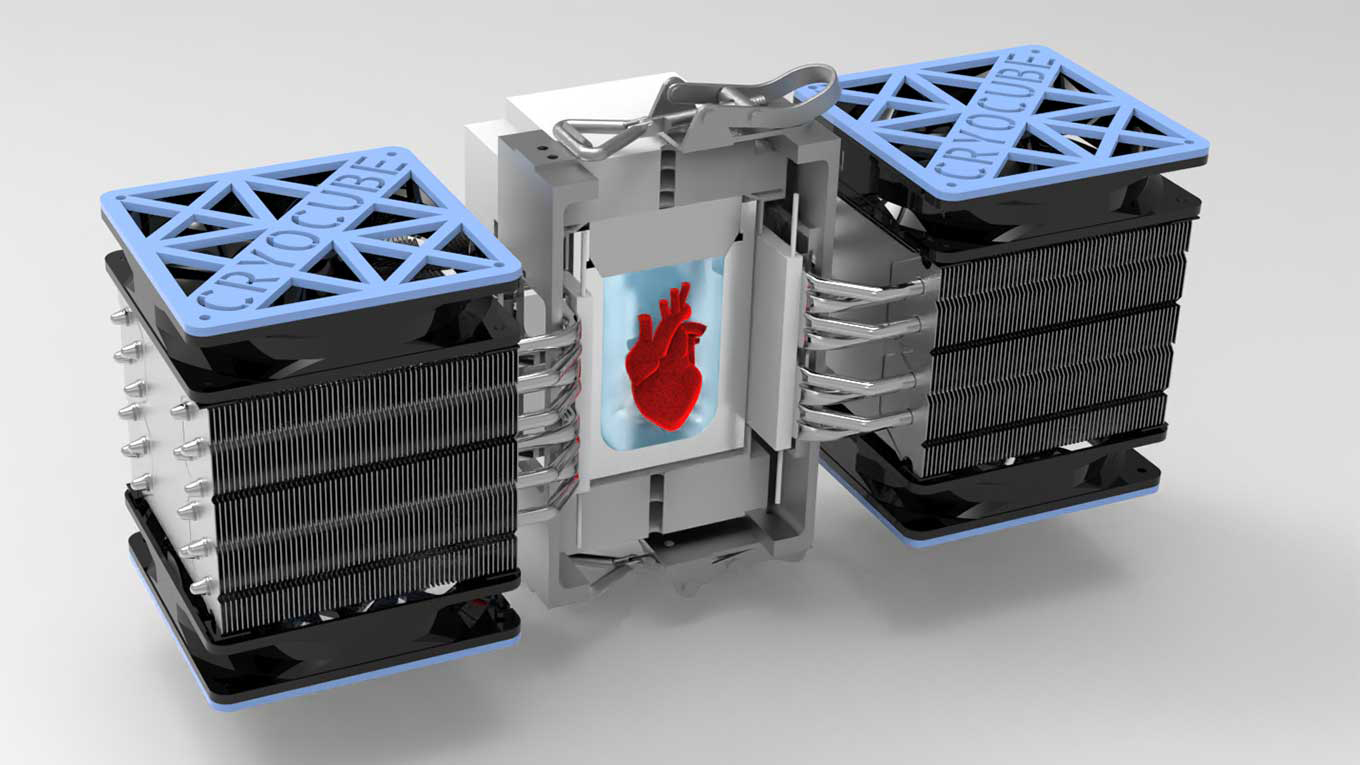

Illustration of isochoric chamber that supercools heart tissue to subfreezing temperatures without ice formation. (Image by Anthony Consiglio/UC Berkeley)

Illustration of isochoric chamber that supercools heart tissue to subfreezing temperatures without ice formation. (Image by Anthony Consiglio/UC Berkeley)Super cool

Preserving donor tissue and organs is a daunting challenge facing the medical field. The viability of a donor heart, for instance, is measured in hours, greatly limiting the recipients who could benefit from a lifesaving transplant. But Berkeley researchers have now revived human heart tissue after it had been preserved in a subfreezing, supercooled state for 1 to 3 days. The method they used, called isochoric supercooling, was pioneered in the lab of Boris Rubinsky, professor of mechanical engineering and of bioengineering. These results also have near-term implications for the preservation and transport of organ-on-a-chip platforms, expanding access beyond the select few labs that can manufacture them for research and industry.

For the study, researchers used cardiac tissue grown from adult stem cells — a heart-on-a-chip system that was developed in the lab of Kevin Healy, professor of bioengineering and of materials science and engineering. The heart-on-a-chip was submerged in a rigid chamber filled with a common organ preservation solution that had been chilled to minus 3 degrees Celsius. Researchers then removed the heart cells from the solution after durations of 24, 48 or 72 hours, and returned them to a warm 37 degrees Celsius. Examination of the heart tissue confirmed that isochoric supercooling had not altered the structural integrity of the heart tissue, nor did it significantly affect the beat rate or beat waveform.

They found that spontaneous beating resumed for 65% to 80% of the cells that had been supercooled for up to three days. Moreover, they found no significant difference resulting from the duration of supercooled preservation.

The researchers — including first author Matt Powell-Palm (Ph.D.’20 ME), Berenice Charrez (Ph.D.’20 BioE), Verena Charwat, and Brian Siemons — emphasized that further work is needed to scale up these results to full organs.

Learn more: Cold-hearted science: Supercooling technique advances preservation of human tissue