Smart and in charge

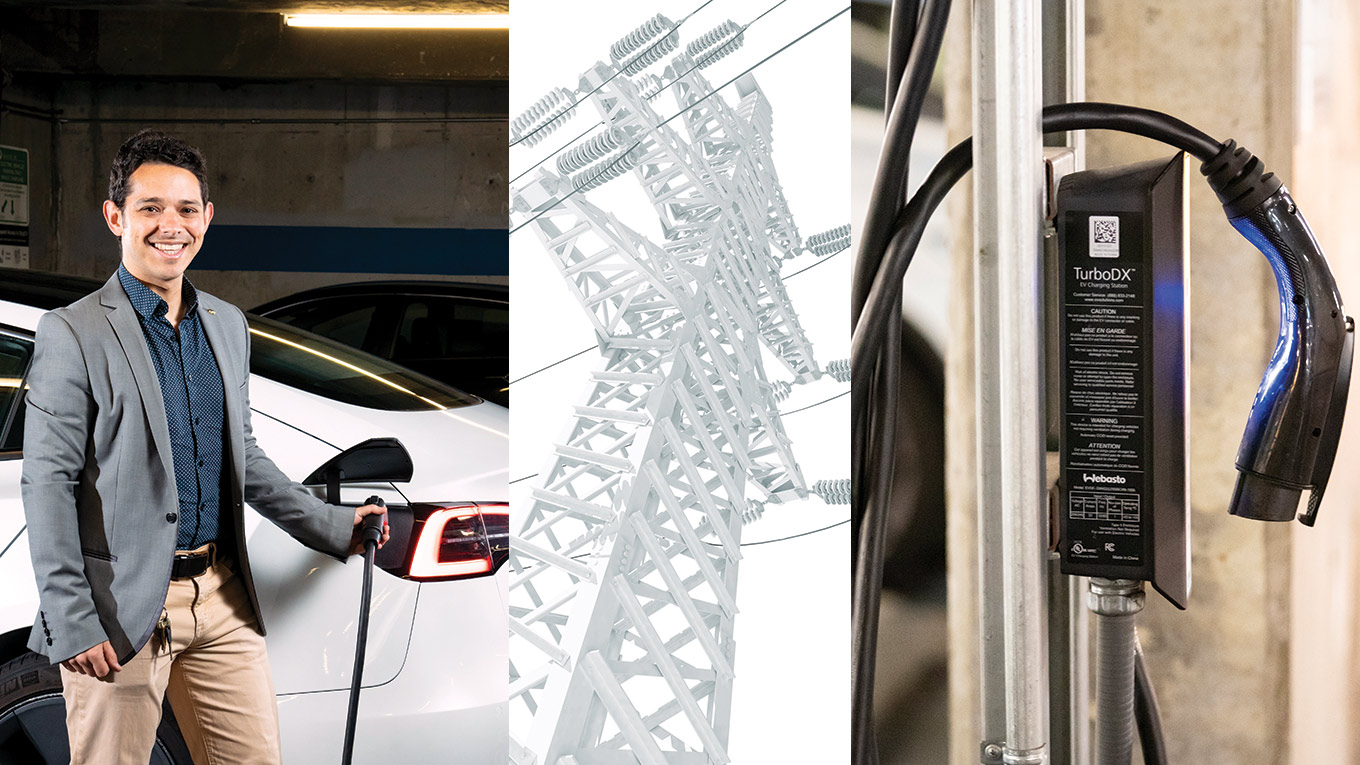

Twice a week, Erin Murphy-Graham drives her electric Volkswagen ID.4 to UC Berkeley’s Recreational Sports Facility (RSF) parking garage and plugs in to one of eight charging ports.

There, the associate adjunct professor of education, who is joined on the ride by her husband, economics professor Bryan Graham, is taking part in a novel project: the Smart Learning Research Pilot for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations (SlrpEV), which aims to provide a blueprint for the future of electric vehicles (EVs) — and more to the point, how best to power them.

For Murphy-Graham, the process is simple and straightforward: using a specialized app, she chooses whether to pay a higher rate to have her car charged quickly or to opt for a cheaper, slower rate. In either case, she schedules a departure time at which she must retrieve her car or face an overstay fee.

SlrpEV’s charges Murphy-Graham’s Volkswagen using machine learning and behavioral economic models to understand, predict and efficiently manage her car’s power needs. Different from other charging station networks, whose prices do not respond to real-time electric grid conditions, SlrpEV gives travelers an “optimized” discount for deciding how much energy and at what speed the vehicle is charged. Optimized pricing, as a result, reduces strain on the electric grid. The process is dictated by algorithms that consider the price and wider outlay of grid electricity use at the moment a car is connected to the station.

The SlrpEV project is of no small consequence. By 2035, the state of California is requiring that all new car and light truck sales be zero-emission vehicles. With that comes a giant and obvious question: How will California’s electric grid be able to handle the influx of 12.5 million EVs?

Overseeing SlrpEV is Scott Moura, the Clare and Hsieh Wen Shen Distinguished Professor in Civil and Environmental Engineering. Collaborating with TotalEnergies SE, Moura spearheaded efforts to bring the chargers to campus in 2020. Since then, SlrpEV has delivered more than 225,000 e-miles to over 200 unique users. As Moura explains, the model provides critical data for designing a system that maximizes the consumer experience in parallel with the objective of grid stability.

“I tell everybody, the products we are creating here at UC Berkeley are people and knowledge,” says Moura, whose engineering training is in controls and optimization. “Within this whole transition to electrifying transportation, we need people who understand not just the technology, but how it intersects with economics, business and infrastructure policy. That is my North Star and center point.”

In the loop

On his smartphone, Moura is able to view real time RSF charger usage. On a late weekday morning in February, seven vehicles are charging. Some of the owners are paying higher rates for the faster charge at maximum power. Others, who have scheduled a departure time and selected the number of miles of range to be added, pay a discounted rate, which grants flexibility to the station in determining charging speed. The researchers have found that, with significant discounts, 80% of users will choose the second flexible option.

Smart charging aligns with California’s attempts to enact the world’s first detailed pathway to carbon neutrality by 2045.

“The deeper discount we give, the more people will accept the scheduled option,” Moura says.

Data from the users’ apps allows the researchers to identify unique preference trends and learn how discounts can best incentivize flexibility. In addition to optimizing prices for users, this data also helps the team determine how to make smart charging stations economically sustainable and discourage users from charging elsewhere — such as at home.

“If we present people with different options, and they have a set of conditions that they’re working in, there’s some probability that they’re going to behave a certain way,” he adds. “It’s basically the same concepts that are used in advertisements.”

The idea is to encourage consumers to schedule their EV’s energy consumption for a time that’s optimal for the grid, instead of when it seems convenient. It’s akin to Amazon offering discounted shipping to shoppers willing to delay delivery of their order (“optimizing their logistics on the back end,” says Moura), and the process is similar to Netflix algorithms that personalize programming recommendations.

“As engineers, we’ve been reticent to put humans in the loop because there’s not some simple equation that describes how they operate,” he adds. “But with certain advancements in machine learning and being able to get data, we now can include them in the loop.”

The evening charging problem

Smart chargers, and especially workplace chargers that can dispense abundant electricity derived from solar power, are expected to temper one of the more pointed criticisms of electric cars: owners are most likely to charge the vehicles at home and in the evening after work, a peak time for energy demand.

Charging during peak demand is one of the worst things for reducing emissions. It requires the grid to use more power from polluting sources, such as coal or natural gas-fired power plants, nullifying the impacts of zero-emission vehicles.

On the other hand, charging in the middle of the day, when solar energy is available, is coincident with the least emissions. Smart chargers, particularly at workplaces, can incentivize behaviors that reduce demands on the grid and capitalize on the availability of renewable energy sources.

This will become more critical as California attempts to enact the world’s first detailed pathway to carbon neutrality by 2045. So-called “net zero” carbon pollution would cut air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions by 71% and 85%, respectively; drop gas consumption by 94%; create 4 million new jobs; and save Californians $200 billion in health costs due to pollution, according to the state’s Air Resources Board. Separately, the goal that 90% of the state is powered by clean electricity by 2035 hinges on investing in charging infrastructures and investments in clean cars, trucks and buses.

But for now, given the dearth of such infrastructure, concerns persist. By 2035, the number of EVs on California roads and highways will represent a 15-fold increase from today. Avoiding brownouts will require increased flexibility in the grid, which is where vehicle-grid integration comes into play.

“We need flexible electricity assets that balance supply and demand, since solar and wind power undulate,” Moura says. “Smart EV chargers are unquestionably one important tool in the toolset. The challenge, moving forward, is to transition our electricity system from large fossil fuel generators to an orchestra of clean energy assets, without suffering from brownouts.”

“A giant battery”

Moura, who drives a Tesla Model 3, is bullish about the future. “We’ve got our transportation system that’s operating, and then we’ve got our electric power grid that’s operating,” Moura says. “These two networks have not been coupled.”

Given that personal vehicles are not in use for 90% of the day, there’s plenty of flexibility for pricing and charging innovation and incentives, Moura says.

“If you understand something about human behavior, people are willing to go for discounts. If we can manage how the vehicle is charged, then putting all of these EVs on the grid is not so much of a burden. They become a powerful distributed energy resource, a giant battery.”

For example, in hot summer months when air conditioning units are stressing the grid, EVs can be paid to reduce or delay their charging. Also, during periods of low demand and clear skies, EVs can be incentivized to soak up solar power during the day, instead of charging at night.

“Within this whole transition to electrifying transportation, we need people who understand not just the technology, but how it intersects with economics, business and infrastructure policy.”

Moura says that EVs can be integrated into the power grid, selling back solar energy to power companies during periods of high demand — a process known as vehicle-to-grid or “V2G.” After feeding leftover electricity from their batteries back into the grid, the vehicles could recharge later, when demand has dipped, and renewable energy is available.

For its part, the California Energy Commission maintains that EVs will not tax the grid. In 2022, EVs used 1% of the power supply; the total will climb to 5% in 2030, and 10% in 2035, officials say.

The Berkeley smart chargers are part of a larger effort to modernize the grid with more renewable energy and flexible resources like energy storage and EVs, says Wente Zeng, who works in research and development at TotalEnergies, which helped develop the smart chargers at RSF and is the lead sponsor of the SlrpEV research. Because a number of drivers lack garages or the ability to charge at home, workplace and public chargers can also make EV ownership more convenient and widely adopted. When it comes to electricity producers and users, Zeng says, “both sides need to evolve and become smarter.”

Slurping electrons

Moura developed SlrpEV in response to growing up in smog- and traffic-choked Los Angeles, and he also was influenced by his time pursuing a doctorate in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan. It was the early 2000s, and hybrid vehicles were beginning to make their way into the market. Amidst his studies, automakers Chrysler and GM went bankrupt. The car industry was in flux.

Associate professor Scott Moura, left, and Charisse Dyer, one of the more than 200 SlrpEV users, at UC Berkeley’s Recreational Sports Facility garage.

“I really got interested in the sustainable fuel, alternative fuel area,” Moura says. “I also realized that I was interested in energy infrastructure, and I didn’t want to become an automotive guy because, who knows, we might not have an automotive industry.”

Moura — who created the pilot project’s name as an homage to the electron-slurping vehicles in the Pixar film “Cars” — says the initial launch of SlrpEV was tough, as campus was shut down due to COVID-19. However, users have been steadily increasing, and there are now plans in the next couple of years to add 25 more smart chargers to campus.

The university does face some challenging limitations, says Seamus Wilmot, assistant vice chancellor and executive director of business operations. Wilmot, who oversees the university’s 6,100 parking spaces, worked with Moura to bring the RSF chargers to the university.

“It’s an old campus, so in many locations we don’t have enough electrical capacity to install EV chargers,” Wilmot says, noting that many of the garages on campus were built in the 1960s. “With load balancing, there may be other ways to provide the EV charging, but on our campus particularly, that’s been one of the challenges.”

Meantime, research through SlrpEV remains in progress, as it accommodates a variety of users, vehicles and constraints. While Moura has optimized the price and power of SlrpEV chargers, the next phase will be to coordinate EV charging with other campus resources.

The technology, he says, could be incorporated into other distributed energy resources on campus, including rooftop solar photovoltaic equipment (technology that converts sunlight into electricity); building heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems; and hot water systems. It’s what he calls a “SlrpEV-EnergyHub.”

For Moura, kicking off the project at Berkeley has afforded the opportunity to gather data under real-world conditions — an effort he hopes will make things better for consumers, and ultimately, the environment: “There’s always some probability that someone says, ‘I’m not willing to play that game.’ Fate is never determined by us, but at least we can shape it.”