Material intelligence

Fallen pinecones lie scattered across wet grass. Shaken free by a powerful overnight storm, they are now soaked, their scales closed tight. A young girl splashing through forest puddles picks one up and carries it home. As it dries, she watches in fascination as the sealed scales gradually splay open. The pinecone changes shape through some mysterious structure hidden inside, like a robot powered by water.

Lining Yao, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Morphing Matter Lab, was that little girl. Growing up in Inner Mongolia, she entertained herself by watching the way plants transform themselves to meet their needs. That early fascination led to a lifelong pursuit. From reforesting lands destroyed by wildfires, to providing robots with the same tactile mastery as humans, to embedding changeability into matter, Yao’s work envisions a future where materials themselves respond through interaction with the environment.

“My scientist side is mostly interested in the morphing phenomenon,” says Yao. “But as an engineer, I’ve really benefited from design practice and thinking, because it connects my work with more people.”

Yao began her career as a designer. Her first academic degree from China’s Zhejiang University was in industrial design, and she later interned at Samsung, where she helped design the interface for the first Gear watches. That experience inspired her Ph.D. thesis at MIT on shape-changing composite material design, which directly informed some of her earliest inventions, such as the ElectroDermis — a wearable biometric monitoring platform similar to a fitness tracker but able to capture and interpret a much wider range of physiological signals.

Today, she foresees a new paradigm in which technology is no longer fixed or static, but able to shift and evolve. In the Morphing Matter Lab, that vision begins with a simple but profound question: What if materials themselves could sense and respond to stimuli, reconfigure and adapt as needed?

Self-burying seeds

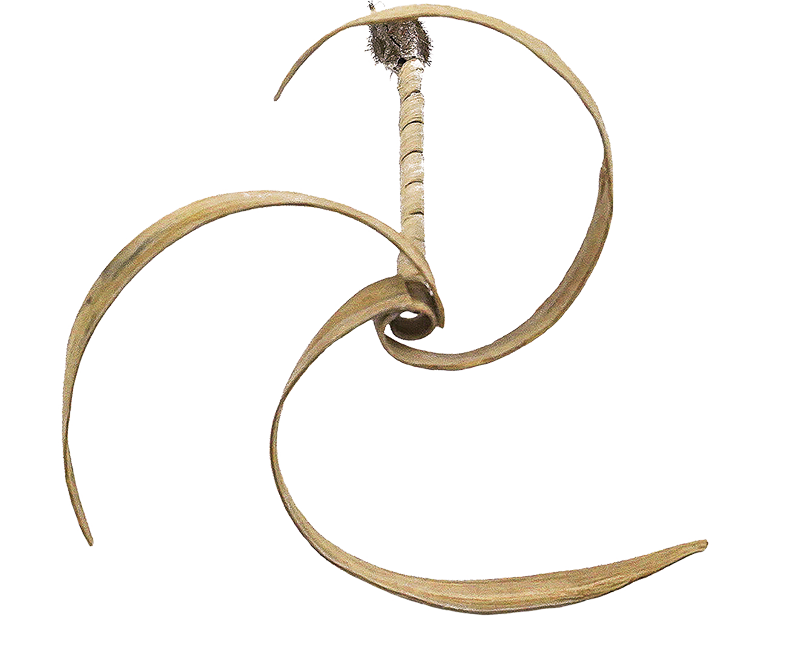

Erodium gruinum (Erodium) is a flowering herb native to Europe, North Africa and parts of Asia, and it is now found throughout North America as well. It’s a common plant with a remarkable feature: The seeds have one long awn that coils like a corkscrew when dry and unravels when exposed to moisture. This action can cause the seed to push itself into the ground, better positioning the plant for germination. Now, together with her collaborators, Yao has set out to mimic and refine Erodium’s design, harnessing its mechanics to help disperse and plant seeds of other species.

E-SEEDs begin as thin strips of maple or oak bark that are soaked in a chemical bath and then mechanically molded into intertwined spirals. Whereas an Erodium seed is like a corkscrew, an E-SEED is coiled even more tightly, like a spring. A pod containing a plant seed is affixed to one end of the spring, while three long, curved bristles, or tails, are at the opposite end. These tails prop the seed upright at an angle of some 25–30 degrees. As the coiled body and tails absorb moisture, the wood begins to untwist; this combination of energy stored in the tight spring working against the stabilizing force of the long tails causes the seed to be drilled into the soil. The idea first occurred to Yao while studying moisture-triggered morphing in plants as part of her Ph.D. studies.

“I was fascinated by Erodium and thought: What if we could learn from this natural intelligence to bury seeds of our own choosing for rapid, large-scale deployment from the air?” says Yao.

At the back of Yao’s lab lies a large room lined with benches that are cluttered with wood shavings, while an array of tools hangs from the walls. The air carries a strong fragrance of moist soil, the aroma coming from a tray of dirt collected from the Sierra Nevada. With this soil and artificial rain, Yao performs preliminary tests of the drilling action of the seed pods.

The ability of seeds to implant themselves in soil relies on their orientation. Yao and her team found that, when deployed aerially, E-SEEDs land upright 90% of the time, while Erodium seeds land flat against the ground 80% of the time, nullifying their twisting action as a burying mechanism. This difference proved decisive: On flat terrain, E-SEEDs successfully implanted themselves into soil 80% of the time, while Erodium’s success rate was 0%. The Erodium seeds fruitlessly rolled themselves back and forth across the flat terrain, searching for crevices that weren’t there.

This June, Yao’s team conducted a test deployment of E-SEEDs with consultation from Ehren Moler, an assistant professor at James Madison University who studies ecological restoration. Traveling to the University of California’s Blodgett Forest Research Station, they tested E-SEEDs against unmanipulated Douglas fir seeds, deploying both varieties into protective enclosures and monitoring plant development. Their findings showed that E-SEEDs promote earlier germination of seedlings than the unmanipulated fir seeds.

Are E-SEEDs the solution to reforesting wildfire-devastated lands? It’s too soon to say, according to Moler. The gold standard in reforestation is seedling planting performed by human hands because seedlings often have a much higher survival rate than sown seeds. We won’t know if E-SEEDs measure up until large-scale tests are performed across many ecological conditions and on unprotected terrain, but Moler says that they will certainly be a welcome addition to the reforestation community’s toolkit because of the substantial time and resources required for seedling planting.

“Seedling planting is too slow to keep up with the pace of reforestation demand and isn’t physically possible in every location, so E-SEEDs are very promising,” says Moler.

E-SEEDs might have the opportunity to prove themselves equal to seedling plantings, especially when their seed pods are engineered to carry fertilizers or symbiotic organisms like insecticidal nematodes and mineral-conducting mycorrhizal fungi. In fact, Yao has already demonstrated that, when implanted by E-SEEDs, dehydrated nematodes can revive, emerge from the seed pod and take up residence in the soil nine days after implantation. She’s also experimented with adding hydrogel to provide the seeds with additional moisture and small sensors to monitor soil conditions, with the aim of designing a self-sustaining seed delivery system.

“There’s a lot of engineering detail in the pod, because we’re trying to create a miniature ecosystem around the seed,” says Yao.

Sensitive robots

Yao’s team is also working to solve a longstanding challenge in robotics — how to move objects reliably without dropping or damaging them. While AI systems like large language models can mimic human writing using all the content on the internet, there’s no vast trove of tactile data that can train robots on how to grasp a piece of soft cake without smashing it. Part of the problem, Yao says, is that — unlike humans, whose skin has abundant sensory nerves that provide tactile feedback — robotic manipulators have traditionally been made from smooth, unyielding materials that can’t directly assess the things they attempt to grip.

Now, together with Ph.D. student Tianyu Yu and her colleagues, Yao is developing ways of making something like skin for robotic hands, what they call MorphingSkin. It’s a strip of semi-transparent silicone with embedded electrodes and a series of nodules that can extrude or deflate. At the most basic level, the skin is an electro-osmotic pump — the fluid inside is mobilized by an electric current rather than any mechanical action. The mobilized fluid redistributes itself within the skin, creating a surface of soft nodes or suction cups.

Yao’s team has demonstrated how this changeable surface, when applied to a robotic gripper, mimics a human finger or palm by creating just the right resistance for the material it grasps.

If that material is something delicate, like a flower, the nodes extrude to create a yielding, textured surface that can hold without clamping. If the gripper needs to pick up one plate from a stack, the skin on the gripper’s clamps deflates into a suction cup that can adhere to the top of the plate. It then moves it off-center just enough to allow both clamps to get a good grip.

The team has also applied MorphingSkin around the circumference of a small, cylindrical desktop companion robot. The extruding nodes of the skin function as locomotors to propel the robot along a flat surface, and the action can be reversed to allow the robot to climb vertical surfaces. The robot is programmed with simple social behaviors like a Tamagotchi-style pet, but they are working on more utilitarian models.

“It’s very exciting to be working on this small robot,” says Yu. “It may be something that can move in very tight spaces to detect or retrieve things. It’s a new idea that I think will inspire people.”

The team discovered far more applications for the technology than they first imagined. At a recent symposium, they demonstrated some of these possibilities, including a multimodal wearable — a wrist brace made from MorphingSkin that provides haptic feedback to human users. Its extruding nodes can provide tactile guidance on movement and breathing during meditation or yoga, or even provide course directions for cyclists. The wrist brace also integrates sensors with a display system, composed of a pump filled with colored fluid that functions like a meter, that can provide information on heart rate or workout progress.

Saving time, reducing waste

A common frustration with 3D printing is the time it takes to produce complex objects. For example, Yao found that something as simple as printing a flower on a 3D printer might take as long as nine hours. She wondered: Might it be quicker to print out a flat shape that refolded itself into a flower? That question led her to pioneer a technique she calls Thermorph. Requiring no special technology, only custom code, Thermorph embeds stress and directionality into 3D printed objects, allowing them to change shape when activated.

The process changes the speed and direction of the print head of any standard 3D printer, causing polymer chains within the plastic to be stretched out when printed. This process embeds potential energy within the molecule that is released when sufficient heat is applied, as the polymer chains return to their bunched-up, low-energy state. When embedded at key points, these stresses amount to programmable matter. Known as 4D printing, because it includes a time element, this approach dramatically reduces production time. Now, the flower that once required nine hours to print can form itself in just 30 minutes.

Yao has also demonstrated how the technique could be used to reduce waste. Most mass-produced furniture is shipped disassembled to reduce container size, but the extra foam and cardboard packing inside might take up just as much space as the shipped item. Yao has designed a Thermorph chair that could be shipped completely flat, requiring no excessive packing material, and transforms itself into furniture with only the applied heat of a hair dryer.

Using this technique, she’s also designed emergency shelters that assemble themselves under the heat of the sun and has experimented with shape-changing circuit boards. Product designers are often constrained by the need to incorporate flat rectangular circuit boards, and Yao hopes that her morphing circuits will inspire designers to come up with some surprising new products.

Possibilities like these are exactly what drives the research in the Morphing Matter Lab. Since arriving at Berkeley, Yao has drawn students from across disciplines — designers, chemists, mechanical engineers, even chefs — who are rethinking materials. Yao says that, just as she benefited from art and design experience, the lab benefits from this convergence of perspectives, pushing the boundaries of what engineered matter can achieve. Ultimately, she believes her approach will lead to better solutions for humans and the environment.

“There’s curiosity-driven research, and then there’s use-driven thinking — the designer’s mindset,” says Yao. “I always ask my students: Who are you benefiting by introducing this knowledge into the world?”