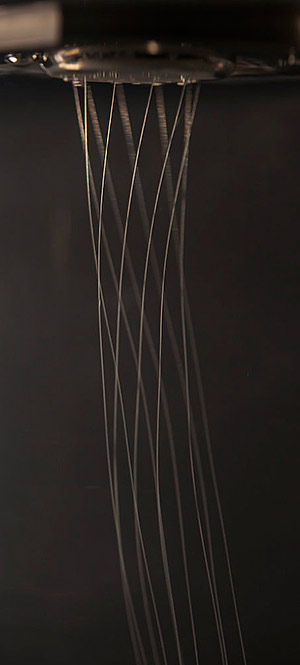

In their Emeryville laboratory, Bolt Threads is developing products from protein strings that mimic the composition of spider silk, one of nature’s most durable fibers. (Photo courtesy Bolt Threads)

In their Emeryville laboratory, Bolt Threads is developing products from protein strings that mimic the composition of spider silk, one of nature’s most durable fibers. (Photo courtesy Bolt Threads)Improving the work of silkworms and spiders, with yeast

Where some people see mere cobwebs, David Breslauer sees nature’s most robust fiber. A 2010 graduate of the joint UC Berkeley-UCSF Graduate Program in Bioengineering, he has spent years studying spider silk, the stuff of webs and cocoons, in order to better understand how it’s made.

When fermented with sugar and water, genetically modified yeast produces protein strings that can be spun into fibers for weaving into fabrics and garments. (Photo courtesy Bolt Threads)

Spider silk, a protein fiber spun exclusively by its namesake, exhibits a unique combination of strength and elasticity that makes it tougher than steel and Kevlar, and is a potential game-changer in a broad range of applications including bulletproof vests, surgical sutures, garments and apparel, ropes and cables, waterproof electronics cases and more.

Researchers have been trying for decades to come up with an affordable way of mass-producing spider silk on a commercial scale, including farming spiders and milking it from genetically modified goats. But no one has succeeded at harnessing the material — until now.

While at UCSF, Breslauer met two other doctoral students, Dan Widmaier (chemistry and chemical biology) and Ethan Mirsky (biophysics), who were also interested in this niche field. In 2009, they founded Bolt Threads, with Breslauer (whose father, George, was Berkeley’s executive vice chancellor from 2006-2013) serving as chief scientific officer (CSO), Widmaier serving as chief executive officer and Mirsky serving as vice president of operations.

It would be five years before they announced the development that brought them together: producing spider silk without spiders, by finding a way to create and assemble its constituent proteins. Today they are poised to become the world’s first to bring its benefits to the masses, in the form of (initially, at least) high-performance fabrics, an application that Bolt Threads decided would have the biggest early impact.

The key to the company’s innovation actually has more to do with beer and cheese than arachnids. Bolt Threads has genetically modified a yeast that, when fermented with sugar and water, generates silk proteins similar to those produced by spiders. These protein strings are then spun into fibers for knitting or weaving into fabrics and garments.

Unlike traditional silk clothing made from silkworms, Bolt Threads’ engineered silk holds its color well and is amenable to machine washing and everyday wear, Breslauer says. “Traditional silk has a great utility where it’s used, but it doesn’t see broader usage because of its limitations.”

David Breslauer (right) with his father George, then Berkeley’s executive vice chancellor and provost, at his graduation in 2010. (Photo by Bay Area Event Photography)

Bolt Threads says its fabrics are still as soft, warm and breathable as those made by silkworm silk. And by controlling the amino acid sequence of the silk proteins it produces, it can enhance additional qualities like stretch, strength, weight and water resistance, expanding upon the seven basic types of natural spider silk with virtually limitless variations tailor-made for fashion, exercise and well beyond. As CSO, Breslauer leads the design, production and testing of new materials with desired performance properties.

“We see it as a brand new category of fibers,” he says.

Today the company has nearly 50 employees, including Berkeley alums from engineering and chemistry, and is already producing test runs of fibers from its 32,000-square-foot headquarters in Emeryville. Bolt Threads also has a fermentation partner in Michigan and manufacturers in North Carolina, long the epicenter of the nation’s textile industry.

With a technical solution and sufficient funding in hand — including $40 million from Silicon Valley venture capital firms Foundation Capital, Formation 8 and Founders Fund — the company is ready to break into the apparel industry in a big way. Their first fabrics will reach store shelves sometime next year. In the meantime, Bolt Threads is enjoying its coming-out party, including recent articles in Wired, Bloomberg Businessweek, Fortune, Fast Company and Forbes.

Whether Bolt Threads will one day return to designing for the likes of bulletproof vests and surgical sutures — two applications that attracted interest from two of the trio’s early funders, the U.S. Army and the National Science Foundation — remains to be seen.

Susan Muller, a chemical engineering professor in Berkeley’s College of Chemistry and an informal adviser to Breslauer, says that as with other emerging technologies like 3-D printing and artificial intelligence, it may well be too soon for anyone to tell just where Bolt Threads and its technology are headed. “There’s not been a lot of an innovation in materials for textiles in a long time, so it’s hard to guess where the best applications are, where the killer app is,” she says.