Concrete knowledge

Having withstood an aggressive seawater environment for over 2,000 years, the concrete the Romans developed for Mediterranean harbors is remarkably durable—particularly when compared to its modern concrete counterpart, known as Portland cement, which can start deteriorating within 50–70 years. Now, Berkeley scientists have learned the secret of exactly what makes Roman seawater concrete so long-lasting.

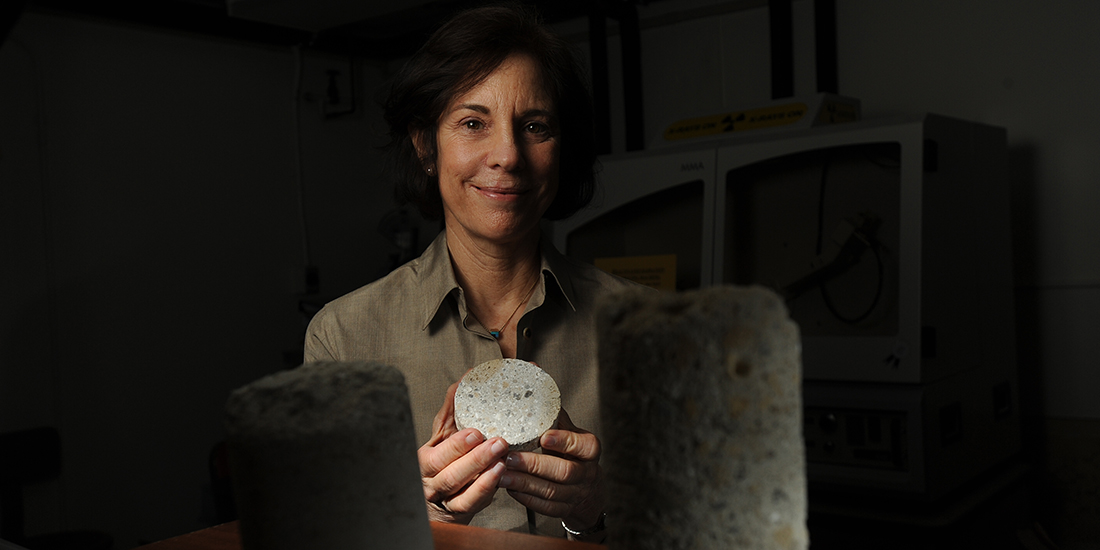

Chris Brandon of ROMACONS collects a sample from a breakwater in Pozzuoli Bay, near Naples, Italy. (Photo courtesy J.P. Oleson)

Lead research engineer Marie Jackson, working on a team headed by civil engineering professor Paulo Monteiro, analyzed samples of a Roman breakwater near Naples and found that its binder—calcium-aluminum-silicate-hydrate (C-A-S-H)—results in an extraordinarily stable material. The Romans made their concrete with a lime and volcanic ash mortar, incorporating chunks of volcanic rock. When this mixture was submerged in seawater, exothermic reactions produced heat in the massive concrete structures; the elevated temperatures encouraged the development of a rare cementitious mineral, Al-tobermorite, which contributed to the material’s long-term cohesion.

Compared to ancient Roman concrete, the manufacture of Portland cement concretes requires more fuel and releases larger amounts of carbon dioxide. With these latest findings, the scientists are looking for ways to develop greener, longer-lasting modern concretes using the expertise of ancient Roman engineers.