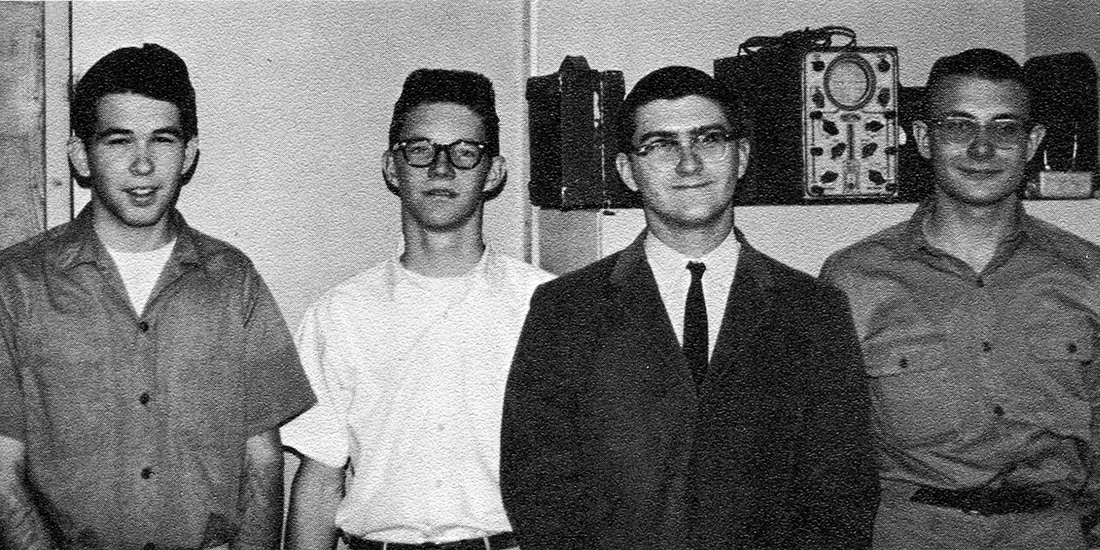

Radio Kal engineering staff (from left to right) Sam Wood, Dinnis Seguine, Mike Silverstone and Lee Felsenstein. (Image used with permission from the 1964 Blue & Gold Yearbook)

Radio Kal engineering staff (from left to right) Sam Wood, Dinnis Seguine, Mike Silverstone and Lee Felsenstein. (Image used with permission from the 1964 Blue & Gold Yearbook)Berkeley sounds: The early days of KALX

The radio station known as KALX began life in 1962 in the basement of Unit 2, a residence hall on Dwight Way. It had at its disposal a collection of records (mostly classical), a couple mics, a cheap recorder and the semblance of a mixing board built into an old cigar box.

Then called Radio KAL, the station was conceived and initially operated entirely by two plucky Unit 2 residents who had launched the effort upstairs in their dorm room: electrical engineering major Jim Welsh (B.S.’67 EECS) and geology major Marshall Reed. Foreshadowing future tactics, the pair talked their way into Unit 2’s basement listening rooms— otherwise intended for students to play records or practice their instruments — surreptitiously ran cable and homemade transmitters throughout the building, and recruited a residence-hall handyman who not only offered keys and tools but also later helped them build furniture. Thus was KALX born.

Welsh and Reed are no longer around to tell of these seminal moments in Berkeley radio. But they’re practically gospel to electrical engineering alumnus Sam Wood (B.S.’68 EECS), who became their willing and able accomplice shortly after arriving at Berkeley in the fall of 1963. Soon, like Welsh and Reed and the rest of the small Radio KAL inner circle, Wood would make a habit of going to relatively absurd lengths to both grow and protect the station during its first five years, thanks to the long leash of university administration.

Some of the details are lost to history. But many remain vivid in Wood’s mind more than 50 years later — like the midnight reconnaissance missions they would run to salvage resistors, capacitors, tubes and transformers from various departments on campus, for use in constructing consoles, transmitters and other radio equipment.

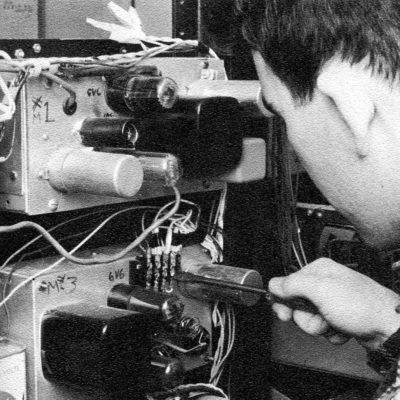

Building the forerunner to KALX radio. (Image used with permission from the 1964 Blue & Gold Yearbook)

“The products we were making we could not afford,” Wood says. “We figured out designs by talking to people and doing the work ourselves. We had to collect parts from different departments, and each department would have large surpluses of some particular thing. They’d just be lying around loose. We put together a shopping list, and then we’d go out and collect what we needed.”

The same principle applied to installing equipment in other dorms and campus buildings as the station furtively extended its reach. Transmitters built on aluminum cafeteria trays were stashed in cleaning closets and storage rooms, one for every couple floors, and cables run from top to bottom.

“The rule was, the university wouldn’t let you do anything, but after 10 or 11 at night, everybody went home,” Wood says. “If wires somehow got into conduits, then nobody cared how they got there.”

Much of the wire and cable itself, hundreds and hundreds of feet of it, was scrounged — with approval — from the floor of the Cow Palace in Daly City after the 1964 Republican National Convention. Wood and Co. also later received tacit approval from the electrical engineering department to use its machine shop, where they fabricated the face of their first professional-grade console.

Some of their accomplishments live on in more than just memory, like the wiring and other equipment still ensconced in walls, closets, basements and attics across campus. At his 40th reunion in 2008, Wood checked a few known caches; still there, he found: “It was amazing.”

By late 1964, thanks to remote-broadcast equipment designed and installed with Wood’s help, Radio KAL had established itself as a competent chronicler of Cal sports, performances and other campus events. With the Free Speech Movement dawning at Berkeley and Radio KAL ready to leap from the dorms to the public airwaves, the station’s most important work was yet to come. But it almost didn’t happen. Due to the political and social climate of the time, the UC Regents denied Radio KAL’s request to apply to the FCC for an FM license. “Everybody was scared to death that if the station got taken over by radical groups, it would really destroy the image of the university,” Wood says.

Two years later, under the dubious assumption that the signal wouldn’t reach as far as San Francisco, the university finally acquiesced and allowed the station to apply for a low-power broadcast license. The students used university funding to purchase a 10-watt transmitter. Wood and UC Chief Engineer Al Isberg, who had previously gone to bat for the station with university officials, built an antenna and mounted it atop Eshleman Hall. Wood also helped select the call letters KALX, and signed off on the official paperwork that got the new station running in October 1967.

Concerns about politics and free speech didn’t end there, however. In fact they intensified, with the station still independent and in charge of its own fate despite a considerably higher profile. “People would come in with an agenda, radical groups on the left and the right, that wanted to use the station to rile people up. There was no Internet then; this was how you did it — through radio stations,” Wood says. “We had to keep a very stern hand on everything. Since the area was so political, there were groups that wanted to take over the station. We had to be very careful.” If they weren’t, the station risked losing its license.

Wood, a Sacramento native, says his own views at the time were “pretty conservative” — by 1960s Berkeley standards at least — and he was primarily interested in avoiding political dealings altogether. To keep the station’s hands clean, he and Welsh took a couple of extreme, yet ingenious steps. They established a private phone line running from the studio to their off-campus apartment across the street that allowed them to cut the signal to the rooftop transmitter if anyone attempted a takeover. And they wired the studio so that all the microphones were hot all the time, meaning Wood and Welsh could remotely monitor conversations for intent to broadcast material that could get the station in trouble. On at least two occasions they took KALX off the air until things cooled off, Wood says.

The station did, however, play a valuable role broadcasting and in many cases recording political talks and free-speech events in Sproul Plaza. KALX microphones appear regularly in historical photos of the era, and Wood was even subpoenaed to testify to the veracity of the station’s tapes of talks by members of the Oakland Seven, anti-draft demonstrators who were indicted on conspiracy charges in 1968, taken to trial and ultimately acquitted.

After Wood graduated in 1968, and Welsh died from cancer, the station moved into new hands. Ideologically motivated threats finally caught up with KALX, leading to its temporary disbanding and removal from campus on multiple occasions in the early and mid-1970s. By the late 1970s, though, it was back for good.

But no one did it quite like Wood, Welsh and Reed in those early years — nor is anyone likely to ever again, at Berkeley or anywhere else. Despite securing modest budget allotments from both the chancellor’s office and ASUC, the station didn’t simply slip through the cracks in the 1960s, Wood says; it was in the cracks.

“We weren’t in anybody’s chain of command, and that’s how we were able to do it. Everything was freelance. If we had to follow bureaucracy and procedures,” he says, “there’s no way this would’ve happened. You could never do any of the stuff we did then today.”

Wood’s penchant for independent thinking continued to serve him well after graduation, when he went to work in the telecommunications industry. Over the years, he has racked up a lengthy list of accomplishments and helped pioneer numerous network technologies, including designing the first self-contained PBX phone system and attaining numerous patents.

Now living in Los Altos Hills, Wood continues to work as a consultant designing innovative products and solutions for technology companies. “Radio is great,” he says, “but telephone systems are even neater.”