Plate piles keep levees intact

Hamed Hamedifar, Ph.D.’12 CEE (Photo by Wendy Wolfson.)

In the basement of Davis Hall, Hamed Hamedifar (Ph.D.’12 CEE) is rattling scale models of levees on a shake table, subjecting them to vibrations replicating the magnitude 6.9 El Centro earthquake of 1940. Hamedifar is designing a plate pile system, rectangular plates affixed to three-yard beams, to bolster the strength of levees in places like the California Delta.

The U.S. Geological Service predicts a 63 percent probability of a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake in the Bay Area and Delta region sometime in the next 30 years. The Delta, which supplies two-thirds of California’s drinking water and irrigation, is particularly vulnerable to levee failure because the aging infrastructure is in a low-lying and seismically active area. A levee failure in Sacramento could cause flooding between 10 and 24 feet deep.

“It always bothers me when I see people get hurt by something engineers could prevent,” says Hamedifar, a research specialist at Berkeley’s Resilient and Sustainable Infrastructure Networks (RESIN) project. “I decided to work on something that could reduce failure.”

Hamedifar, the son of a building contractor, grew up in Tehran but moved to America at the age of 19 and became a U.S. citizen. He earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees in civil engineering at Berkeley and completed his Ph.D. last year under the supervision of CEE professors Juan Pestana and Robert Bea.

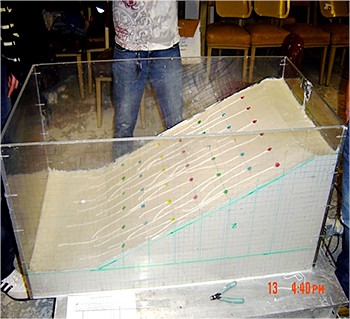

Hamedifar’s plate pile model is tested on a shake table in Davis Hall. (Photo by Wendy Wolfson)

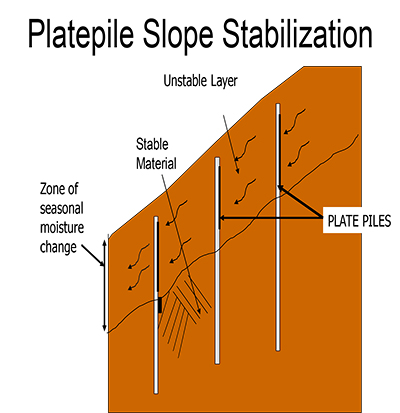

For one of his research projects, Hamedifar borrowed a technique of using plate piles to prevent landslides that was invented by Richard Short, a geoengineering lecturer at the college and Hamedifar’s mentor, and adapted it for embankments and levees. “It is a very reliable method—cost-effective, environmentally friendly and proven to work,” says Hamedifar.

The plate piles are embedded into a levee in a staggered, evenly spaced array. Imagine billboards placed evenly apart, rising incrementally in accordance with the slope of the levee. “The basic concept is that the plate acts to reduce the driving force of the upper soil mass of the embankment and transfers that load through the pile to the subsurface layers, so it won’t cause the levee to fail,” says Hamedifar.

Plate piles are made out of fiber-reinforced plastic or aluminum. Installation, which can take place year-round, requires a backhoe, an excavator and a hydraulic hammer or air hammer.

In each installation, a civil engineer needs to determine the soil structure—because plate piles work for most soils but are unsuitable for soft, organic substrates, such as peat.

Hamedifar borrowed a technique originally designed to prevent landslides and adapted it for embankments and levees. “It is a very reliable method—cost-effective, environmentally friendly and proven to work,” he says. (Schematic by Hamed Hamedifar)

Hamedifar estimates that stabilizing levees with plate piles will save time and money. A conventional levee requires three months to build, on average, and construction costs around $15 million. The average plate pile installation would require 10 days from permitting to finished product, and would cost less than $1 million.

Hamedifar examined the geometry of existing levees in Sacramento, Yuba City and Stockton. Using 65 cross-sections, he measured the load behind the levees to determine the safety factor with and without plate piles. “In the majority of cases it showed a huge improvement,” said Hamedifar. “In some cases we had minor improvement, but in all cases we had improvement.”

In repeated tests, levees with the plate piles showed no deformation post-shaking. Without the plate piles, the levees failed, dropping three to four feet. “It is an exact model of what we are doing but scaling it down for levees,” said Short. “There is a lot of science to scaling it down and doing those tests. The uniqueness is the seismic stability.”