Flight delays cost more than just time

WAITING GAME: Passengers bear more than half the cost of domestic flight inefficiencies in terms of lost time and productivity due to delays, cancellations and missed connections, according to a new study commissioned by the FAA and led by UC Berkeley researchers. (Photo by ©ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/EPIXX)

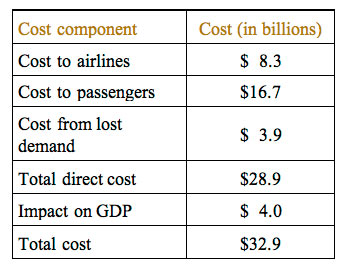

Domestic flight delays put a $32.9 billion dent in the U.S. economy, and about half that cost is borne by airline passengers, according to a study led by UC Berkeley researchers and released last month.

The comprehensive report, Total Delay Impact Study, analyzed flight delay data from 2007 to calculate the economic impact on both airlines and passengers, including the cost of lost demand and the collective impact of these costs on the U.S. economy. The report was commissioned by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to clarify key discrepancies in earlier studies.

More than half of the total cost, or $16.7 billion, was borne by passengers, the new study found. This number was calculated based on lost passenger time due to flight delays, cancellations and missed connections, as well as expenses for food and accommodations as a result of being away from home.

The study found that airlines with high rates of delay also have higher operating costs overall. The $8.3 billion direct cost to airlines included increased expenses for crew, fuel and maintenance, among others. Inefficiency in air transportation also had indirect effects on the U.S. economy, the report said, decreasing productivity in other business sectors and reducing the 2007 U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by $4 billion.

“This is the most comprehensive study done to date analyzing the monetary cost of airline flight delays,” said Mark Hansen, UC Berkeley civil and environmental engineering professor and the study’s lead researcher. Most previous studies have focused on cost to airlines, Hansen said, but the new study analyzed the complex relationship between flight delay and passenger delay and considered how degraded service quality affects demand for air travel.

“Before this work, no one actually analyzed the data to see how flight delay affects airline cost or passenger lateness,” Hansen said. “While there are a lot of widely available data on flight delays, passenger itineraries and airline costs, this is the first attempt to fully exploit that information to measure the impacts of delay.”

Hansen is a director of the National Center of Excellence for Aviation Operations Research (NEXTOR), a multi-university research center of which UC Berkeley is a core partner. Also participating in the research were NEXTOR affiliates MIT, George Mason University, the University of Maryland and Virginia Tech as well as The Brattle Group, a consultancy. Hansen’s doctoral student Bo Zou also contributed extensively to the study.

The study looked at costs not previously tallied as part of a single data set, including:

- Costs to passengers based on time lost to flight delays, cancellations and missed connections

- Costs of padding schedules, the hidden delays airlines build into their schedules

- Costs of forced rescheduling due to runway capacity limitations

- Cost to passengers of additional time spent away from home because of anticipated delays

- Cost of lost demand from potential customers who used alternatives like driving or video conferencing to avoid airline delays

- Impact of delays and cancellations on the GDP, based on lost productivity

Researchers used an innovative method to calculate the effect of flight delays on airline passenger costs. Such estimates have previously used a straightforward accounting method, assuming, for example, that if a plane carrying 100 passengers were delayed 10 minutes, the delay to passengers would simply be 1,000 minutes.

HIGH COST OF INEFFICIENCY: In calculating the direct cost of domestic flight delays, the Total Delay Impact Study used data from 2007 and employed novel accounting methods to calculate how different flight delay scenarios might affect airline passengers differently.

“The method we used more closely reflects the reality that a given flight delay can affect various passengers differently,” said Cynthia Barnhart, interim dean and professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT’s School of Engineering, part of the MIT-George Mason team that focused on passenger delays. They also considered the phenomenon of people spending extra time away from home in anticipation of delay.

“If I have a meeting that begins at 10 a.m. Tuesday in Washington, I would likely fly out from Boston on Monday night rather than early on Tuesday, just to ensure that I arrive on time,” Barnhart said. Costs were measured by assigning a standard cost to time, plus other travel expenses.

“The significance of this study is its use of innovative techniques to quantify the total cost of congestion to the aviation industry, the economy and society,” said David K. Chin, director of performance analysis and strategy at the FAA’s Strategy and Performance Business Unit. These techniques created new economic measures for airline schedule padding, passenger delay impact and lost productivity, Chin added.

The new study emphasizes that not all delays can or should be eliminated, especially those due to mechanical failures and severe weather that are necessary to protect passenger safety. But increased scientific knowledge can improve operations and influence policy, Hansen said, providing a framework for decision makers to assess the magnitude of the problem and the need for initiatives to address it.