Dan Garcia, professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences, teaches CS10 at Evans Hall. (Photo by Adam Lau/Berkeley Engineering)

Dan Garcia, professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences, teaches CS10 at Evans Hall. (Photo by Adam Lau/Berkeley Engineering)Making the grade

There’s a quote attributed to Stephen McCranie that makes the rounds on social media every now and then: “The master has failed more times than the beginner has even tried.” The idea is that the learning process demands failure.

That’s what the grading system known as “mastery learning” seeks to facilitate: a process that gives students more room to learn from their mistakes. Students advance through topics only after they master the material for each one, with the aim of achieving thorough proficiency in the subject.

Armando Fox and Dan Garcia, professors of electrical engineering and computer sciences (EECS), are behind UC Berkeley’s pilot run, an endeavor they’ve dubbed “A’s for All (as Time and Interest Allow).”

“I’m not giving away free A’s,” Garcia said. “The whole point of what I’m doing is not grade inflation. It’s exactly the opposite: I’m holding the A bar locked.”

Fixed learning, variable time

“Variable learning is what the whole world lives in,” Garcia said. In the Berkeley-sphere, that means 15-week semesters with a set pace plotted out on a syllabus. The students achieve varying degrees of insight and skill in that ‘fixed time’ span.

Garcia teaches CS 10, an introductory course geared toward non-major students who’ve had little to no experience with computer science. “My class is supposed to be a big tent. Everybody’s welcome,” he said. “Yet at the end of the year, I’ve given Ds and Fs to kids that I’ve been telling, ‘Yes, you can do it.’”

Fox and Garcia truly mean it when they tell students they can do it. “It’s people who just come in with less preparation because of their extenuating circumstances, but are as capable and as interested,” Fox said.

He added that “the incentives to really learn the material are misaligned with the way variable-learning grading works.” When a student is struggling with factors like food insecurity or COVID complications — a couple of issues reported in the CS 10 class — they still face late penalties at the end of the day.

This system leads students to spend more time worrying about the points they’ll receive, instead of focusing on whether they’re learning the material, Garcia explained. Throw in the issue of grading curves, and the current standard’s one-size-fits-all approach is a recipe for a spotty education.

To best prepare students for the workforce, they need to achieve a level of competency, Garcia said: “I want these kids to be at an A level, and I get that I can’t force that on everybody, but I’m going to provide them with an opportunity to get to that A level.”

An aha moment

When the Berkeley team first learned about mastery learning at a professional development series on grading for equity, the presenters weren’t talking about auto-graders. There was talk of paper-based retake exams and grading them by hand.

“Grading for equity sounds great,” Fox said. “But you realize how much work it would be if you had to devote human TA and instructor efforts to actually follow through.”

It just so happened that Fox and Garcia had learned about a platform called PrairieLearn that enables real-time grading for questions that are automatically generated. Students can plug away at different variants of the same question until they achieve “mastery.” By using this system, additional grading for retakes wouldn’t cut into TA and instructor time.

“That’s what Armando and I brought to this,” Garcia said. Suddenly, the implementation of mastery learning didn’t sound so far-fetched. “Technology has made it feasible to actually think about doing this at scale,” Fox added. “And that just wasn’t true even 10 years ago.”

This aha moment made Fox and Garcia feel that they “could really be at the center of it all,” as the latter put it. Now, the team is working to make Berkeley one of the leaders in this space.

In 2020, the professors received a $650,000 grant from California Educational Learning Lab in partnership with California State University at Long Beach and El Camino College. With Fox as the principal investigator, the Berkeley team leading this trial run has generated over 2,000 parameterizable question generators (PQGs) for 13 courses across the three institutions.

A new testing ground

Now that exams have become that much easier to automate, Fox and Garcia are looking to the University of Illinois — whose faculty developed PrairieLearn — as a model for the next stage of A’s for All: a computer-based testing facility.

The idea is to allow students to take exams at their convenience. A staff member would be on-hand to supervise test-takers, no TAs needed. Students from any major with a PrairieLearn-backed course could use the room.

This is one of the conversations at the campus level that Fox is involved in. “Even if we don’t get an exam facility for a while, I also think it’s important to have some more formalized and centralized onboarding process and support,” he said.

Garcia sees this supervised environment as necessary for taking A’s for All to the next level.

“Other courses, we haven’t been as confident that we can have students take exams at home with no proctoring,” he said. “So this would support faculty who don’t trust an unproctored exam to be out in the wild.”

Class policymaking

Some policies in Garcia’s class, like offering three chances per semester for exam retakes, have been used successfully in other courses. But others are unique to the A’s for All suite

Perhaps the most revolutionary policy: students are given the option to continue working past the semester to get an A, as long as they fill out an exit survey stating why their circumstances were out of their control.

If a student decides to carry on, Garcia will give the student an Incomplete until they earn the A. If that student decides to stop working toward the A, he will freeze their grade as is. It’s a policy that was easy to roll out in the CS 10 pilot, as the non-majors course is not a prerequisite within CS.

“So what’s the worst that can happen?” he said. “The worst is it rolls back to what they had. They might’ve had a C, so you replace the Incomplete with a C.”

The idea of working past the semester even motivated some students. “Knowing that I had the A’s for All system encouraged me to try harder,” said sophomore Hazel Walia, who now works as an academic intern in the class. “It was nice to have that system, but also, I was thinking, ‘If I go back and try to get an A in a different semester, that’s going to be super stressful.’”

Still, Garcia estimates that 10-15% of students in the A’s for All pilot decided to keep working.

The last piece of Berkeley’s adaptation of mastery learning comes in the form of “flexible extensions.” This policy, already used throughout the EECS department, lays out a process for obtaining short- and long-term extensions.

“So it’s when you need more than the default amount of time,” said Garcia. “And that’s an exceptional situation.”

Work in progress

Given that CS 10 is still a pilot run, Fox and Garcia are fine-tuning the messaging.

The team resolved to place more of the onus on the students in the second pilot semester. “What we’ve done is add a little bit of friction,” he said. “If the assignment is due on Saturday, you don’t just let them miss the deadline and then allow late submissions without any penalty.”

That’s where the flexible deadline forms come in: if a student fills out the long-term extension form, that triggers a meeting with a staff member to check in with them.

“The devil’s in the details of the messaging and turning the knob on requirements,” Garcia said. “It’s less about the A’s for All title. It’s more about not telling them that they have infinite time to do every assignment with no penalty.”

These details extend to the issue of attendance, particularly a mandatory policy that has already moved the dial. Now, students are required to attend discussion and lecture, while labs are due two days after they’re out.

“We’re having much more success with having students in lecture,” Garcia said.

Improving diversity

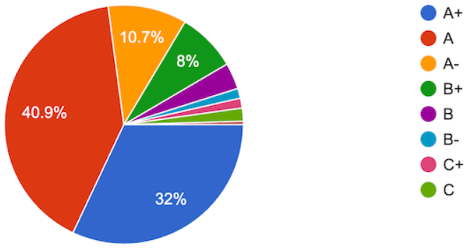

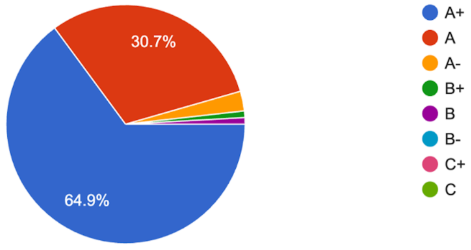

Fall 2022 survey results for the grades CS 10 students wanted before and after learning about A’s for All. (Charts courtesy Dan Garcia)

BEFORE you ever heard of the “A’s for All (as time and interest allow)” policies, what grade DID you want to get in CS10?

AFTER you heard of our “A’s for All (as time and interest allow)” policies, what grade are you willing to work for in CS10?

Back in fall 2022, Garcia conducted a “fascinating” survey with the CS 10 class before telling them about A’s for All. “I asked, ‘What is the grade you want out of this course?’ And it’s an A, B, C. ‘If I get a C, I’ll pass it.’ Then I told them about A’s for All. ‘Now what grade do you want?’ Everybody wanted an A.”

“It sets their aspirations higher,” he said, “so it actually elevates what they want.”

The non-majors CS course is proving to be an ideal site for the A’s for All trial. Following its initial implementation in the fall 2022 semester, Fox and Garcia contributed to a paper on the new grading system’s performance.

“At UC Berkeley, we have repeatedly found that one of the best predictors of student performance in our rigorous introductory CS courses is prior CS exposure, but not all incoming students have the privilege of receiving such exposure,” they wrote. “And it is no surprise that students from socioeconomically challenging situations and/or who are historically underrepresented in CS are more likely to lack prior exposure.”

Garcia notes that the demographics of EECS department students does not match the state demographics for women and students of color. “There’s been a lot of work to try to broaden participation in computer science and in engineering,” he said, pointing toward Assembly Bill 1054, which would ensure all California public schools offer computer science classes. “That’s a really big deal, he continued. “We’ve never had that before.”

Their hope is that by shifting the way introductory computer science courses are taught to students with no background in the field, it could bridge the diversity gap in retention. “We’re better at getting representation into computer science than we are at keeping it there,” Fox added. If lower division classes can help underrepresented students catch up, the playing field will be smoothed out by the time they reach the upper division.

Their final evaluation report found that “URM students and women benefit at a higher rate than majority-group students” with the A’s for All policy. According to Fox and Garcia, 45% of URM students (vs. 31% of non-URM) and 55% of women (vs. 52%) made the most of this policy.

“A lot of students think that CS is for STEM students, and they think that they can never touch that realm,” said Walia. “A’s for All makes you feel that you don’t have to be a STEM student in order to do this kind of work.”