Berkeley Engineering students pull off novel chip design in a single semester. The class shows successful model for expanding entry into field of semiconductor design

Berkeley Engineering students pull off novel chip design in a single semester. The class shows successful model for expanding entry into field of semiconductor designBerkeley engineering students pull off novel chip design in a single semester

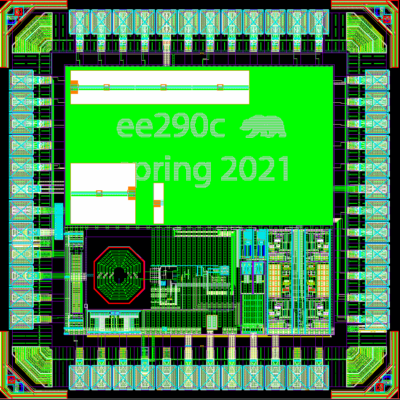

In what could have important implications for engineering education as well as the field of chip design, a class of Berkeley Engineering students has successfully completed the design process — or “tape-out” — for a novel chip that will be manufactured this summer. As part of this spring’s Advanced Topics in Circuit Design course, 19 students with no prior experience in chip design went from basic introductions to tape-out by the end of a four-month period.

The current global shortage of semiconductor chips, exacerbated by the pandemic, has headlined tech industry news. It has spurred proclamations by leaders in China and the United States to make chip manufacturing a national priority. Earlier this year, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to review semiconductor supply chains. Recent legislation passed by the Senate would provide $52 billion for domestic semiconductor manufacturing, research and development.

But even with increased investment, there are still many hurdles, including a lack of prospective chip designers in the U.S. job market that’s been building for years, said electrical engineering and computer sciences professor Borivoje Nikolić, one of three professors co-teaching the class. Though this dearth of ready labor to ramp up chip production and meet escalating demand is itself caused by a range of factors, one potential solution is to expand paths for entry into the field, which has long been dominated by doctoral degree candidates. The success of the circuit design course at UC Berkeley shows that widening the pool to undergraduates could be a viable solution.

“This is a rapidly changing field, and industry wants to always get people with a fresh mindset to bring in new ideas,” Nikolić said. “Our point is that not everyone needs to have a Ph.D. There is room for people with less academic experience.”

Training undergraduate and graduate students to do this sort of work not only takes far less time than a Ph.D. program, but is also much cheaper, Nikolić added. “Let’s bring them to the appropriate skillset so that they can design chips.”

The term “tape-out” refers to the process of recording a chip’s final design and delivering it for fabrication — in this case, to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. This used to be handled via magnetic tape but nowadays happens electronically, a digital file converted to a physical chip.

With the support of Apple, Nikolić, fellow professors Kris Pister and Ali Niknejad, and graduate student instructors Dan Fritchman and Aviral Pandey led 10 undergrads, five master’s students and four Ph.D. candidates through the design and successful tape-out of a novel chip within the span of a single semester. It had never before been done at Berkeley.

“It’s a testament to our students, the teaching assistants and the faculty that we were able to pull it off, but also to the infrastructure for chip design that Berkeley has put together over the last decade,” said Pister. “It’s really quite remarkable, and most people that I talk to don’t believe me when I tell them what we did.”

Niknejad’s take is no less glowing: “In my opinion, what we pulled off in this course was a minor miracle. …Doing a tape-out is a marathon and requires a lot of mental and physical fortitude, something our students have in spades.”

Technically speaking, the students designed what’s known as a “system-on-a-chip,” where multiple components of a computer or other electronic system are combined on a single integrated circuit, or chip. This one includes a microprocessor, encryption device, low-energy radio transceiver (like Bluetooth) and other modules. Nikolić said the chip is of moderate complexity — similar to that found in the new Apple AirTag for tracking and locating other items — and would be made in industry by a dedicated design team using the same 28nm CMOS process.

“We want to encourage students who are interested in hardware to stay in hardware,” says Jared Zerbe, a director of engineering at Apple who oversaw the company’s financial and technical support of the class. “Generally speaking, the semiconductor industry has been the engine of Silicon Valley. We are now entering a golden age of computer architecture. It’s an enormous opportunity for innovation.”

Jeffrey Ni was one of the undergraduate students enrolled in the course. He recently graduated with a degree in electrical engineering and computer sciences but will return next fall for a fifth-year master’s program. He says he hopes to continue pursuing chip design next year, and this summer he will work in the field as an intern at Apple — as will a few other alums of the course. “Getting the chance to make a real chip in a class setting seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Ni said.

On the other end of the class’ academic spectrum was Nayiri Krzysztofowicz, a first-year Ph.D. studying digital circuit design, advised by Nikolić. “If I hadn’t taken the class, I’m not sure when I would’ve been able to tape-out, and it would’ve been a lot slower,” she said. “I think it just propelled me in the right direction, and now I’m finding that all the other research I’m doing is much easier. It really was an incredibly intense crash course for what I needed to know.”