Improving the odds for kidney transplant success

Kidney transplants are, by far, the most common and successful organ transplants worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, more than 70,000 are performed annually. Yet the risk of rejection remains, and about 15 percent of transplant recipients suffer a serious bout of “host versus graft” disease. If severe enough, it can lead to the loss of the new organ. While immune system-suppressing medications help keep the kidney viable, now a team of bioengineering students in the joint Berkeley-UCSF Masters of Translational Medicine program (MTM) have found a way to improve their efficacy with a technology called Kidney Injury Test (KIT).

Schmeckpeper and Nasr represented the Kidney Injury Test team at the Clinton Global University, held at Berkeley on April 1. (Photo courtesy KIT)Problem

Schmeckpeper and Nasr represented the Kidney Injury Test team at the Clinton Global University, held at Berkeley on April 1. (Photo courtesy KIT)Problem

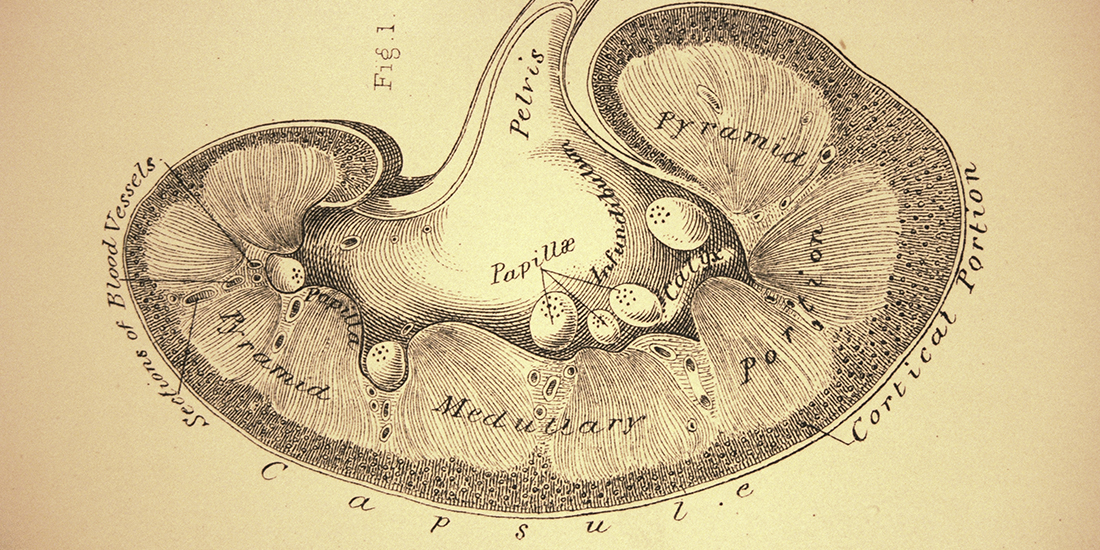

To decide how much immune system-suppressing medication to give a patient, transplant specialists need to monitor the amount of rejection-induced injury in the new kidney. But the two most widely used methods for detection are either slow to detect damage, or risky and invasive.

The current standard for detecting renal rejection is to monitor blood for high creatinine levels, which rise when a damaged kidney is not filtering effectively. Unfortunately, by the time this method indicates a problem, it may be too late to save the organ. The faster, more direct approach is to biopsy the donated kidney, which is costly, invasive and potentially risky.

Solution

A better, earlier indicator of kidney transplant rejection may be found in urine. Recent research shows that DNA fragments from kidney cells damaged by rejection can be found in the urine of transplant patients. The volume of fragments indicates the degree of organ inflammation.

MTM students Michael Nasr, Tyler Schmeckpeper and Josh Yang have teamed up with UCSF’s Sarwal Lab and the Department of Surgery to develop an inexpensive, easy-to-use test for medical professionals that measures urine for levels of damaged kidney DNA.

Potentially, the team’s test will give transplant physicians the clearest window yet into how well they are controlling organ rejection. The patient’s urine baseline is established right after the kidney transplant. After that, routine monthly urine monitoring tracks how well immune system suppression is working to keep the kidney — and the patient — healthy.

The KIT is designed to bind with cell-free DNA. More strands binding means more inflammation.

In an effort to keep costs down, the KIT makes use of materials commonly found in medical clinics and hospitals, and each device will be capable of running many tests.

Result

Nasr, Schmeckpeper and Yang are pursuing a patent through UCSF’s technology transfer office. They also formed a company called KIT and plan to license and eventually commercialize the UC-owned intellectual property.

The project has been recognized for its potential to positively affect world public health by the Clinton Global Initiative University, which invited the three to attend its April 1 meeting on the Berkeley campus.

KIT is also one of 40 semi-finalist teams selected by OneStart Americas, part of the world’s largest life sciences startup accelerator. The team gets a shot at a $150,000 Grand Prize awarded to the project with the most potential to commercialize an idea that improves patient lives.