Sonia Travaglini and her mycology materials in Jacobs Hall. (Photo by Noah Berger)

Sonia Travaglini and her mycology materials in Jacobs Hall. (Photo by Noah Berger)Defining the original smart material

The kingdom fungi contains some of the oldest known terrestrial organisms in the world. Sonia Travaglini, a Ph.D. candidate in mechanical engineering, is studying the properties of part of this eclectic kingdom to find new sources for sustainable composites.

She works with mycelium, which is the sprawling, root-like structure of a fungus that bloom into mushrooms.

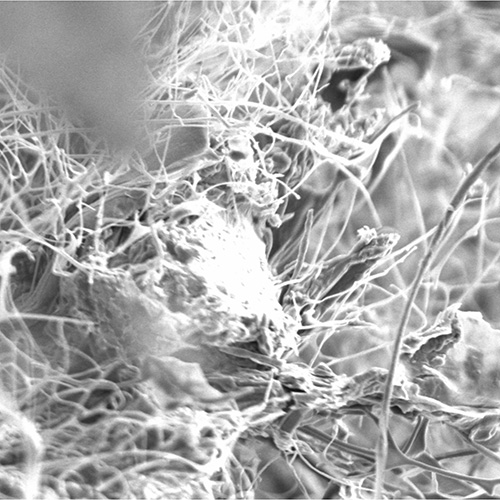

Mycelium hold potential in the materials world because of the way they build their own scaffolding. As they grow, mycelium extrude chitin — the same durable material found in crab shells and beetle bodies — to provide structure to their thread-like tentacles, unfurling in search of food. The hard chitin binds with substrates, forming a natural composite.

A microscopic look at mycelium (Photo courtesy Sonia Travaglini). “When I first saw the material,” Travaglini says, “I thought, ‘this is really brilliant,’ you are basically using mushrooms to grow a material.”

A microscopic look at mycelium (Photo courtesy Sonia Travaglini). “When I first saw the material,” Travaglini says, “I thought, ‘this is really brilliant,’ you are basically using mushrooms to grow a material.”

Travaglini’s research draws on her background in sustainable materials, green manufacturing and human-centered design as an undergraduate in her native England, where she studied product design and innovation and became intrigued by the intersection of materials science and public policy.

“I became really interested in how complex, and sometimes dangerous, many common materials are,” she says about the petroleum-based polymers and their derivatives that are widely used to make plastics. Her interest led to a master’s degree in advanced science technology. “That’s when I started working on polymer recycling projects.”

But materials science is not what brought her to the Bay Area; instead, it was her curiosity about American Sign Language. “I studied British sign language before for fun, and they are surprisingly different,” Travaglini says.

In 2013, while taking sign language classes, she volunteered for a science and technology education outreach program, where she began meeting Berkeley students and faculty who were also involved with the program, including professor of mechanical engineering Hari Dharan. “I said I was interested in recyclable composites and sustainable materials, and was invited to help fellow female engineers on a project at Berkeley, and it just kind of snowballed from there,” Travaglini says.

Soon she was assisting with mycelium materials research. “I was just finding out about the project and really discovering this material,” Travaglini says. She was encouraged to apply to the college to pursue the research as a Ph.D. student.

Working out of Jacobs Hall, and occasionally other labs that contain testing equipment, she is trying to characterize the properties of mycelium. She sources her materials, which come to her in blocks the size of a large cutting board, from Philip Ross, a professor at the University of San Francisco and the founder of MycoWorks, a Silicon Valley-based design and engineering firm finding new uses for mycelium.

While Travaglini tracks emerging applications for this ancient material — which range from packaging and building insulation to furniture and core material for veneered plywood — her research focuses primarily on defining its properties. “Before now, people who used this material intuitively knew how strong it was,” she says “but no one had done the research to say, ‘yes, you can pile so much weight on it before it will fail.’ So that’s what I’m researching — the material properties — particularly its strength, crushability and maximum use temperature.”

Life-cycle sustainability is a major factor that might make these materials economically attractive. “What really surprised me about mycelium is that it can grow off of organic waste,” she says. “So all the waste from the logging industry, or sawdust, or agricultural waste, you just literally combine it with mushrooms and off it goes, and it will create a material.”

“Then we discovered that you can compost this material and it would even digest itself, so after you finished using it, you can use that material to grow a new set of material,” Travaglini says. “I was fascinated, I have never seen such a low-cost, low-impact material.”