Diabetes Management, Simplified

Chris Hannemann (M.S.’08 ME) with glucometer (at left), smartphone and insulin pump, elements of his integrated diabetes management system, which takes the guesswork out of living with diabetes. (Photo by Rachel Shafer.)

Individuals with diabetes live by the numbers. Glucose levels. Insulin dosages. Carbohydrate consumption. Dates. Times. Amounts.

By writing each number in a logbook, they help their doctors manage the disease so they can stay healthy. The recordkeeping is onerous; yet, without complete data sets, doctors may miss trends and recommend ineffective treatments. Without tightly controlled day-to-day management, diabetes can lead to serious complications, including cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, neuropathy and kidney damage.

As a side project to his research in mechanical engineering, recent graduate Chris Hannemann (M.S.’08 ME) began developing a system to help automate the process. His proposal, Integrated Diabetes Management, harnesses Web-based applications and popular mobile devices to make it easier to live with the disease.

“Diabetes treatment involves a lot of guessing because you estimate nutrition information, or you forget to write something down, or you don’t remember the exact details of what happened on a particular day,” says Hannemann, who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age eight. “This takes some of the guesswork out of it.”

The disease, whose cause remains unknown, impairs the body’s ability to metabolize glucose, our body’s primary source of energy. It is treated by administering insulin, the hormone that converts sugar and starches from food into energy the body can use. In type 1 diabetes, the body simply does not produce insulin; in type 2, the body does not produce enough insulin. According to the American Diabetes Association, 23.6 million people in the United States suffer from diabetes, some without even knowing it, and that number is expected to rise to more than 48 million by 2050.

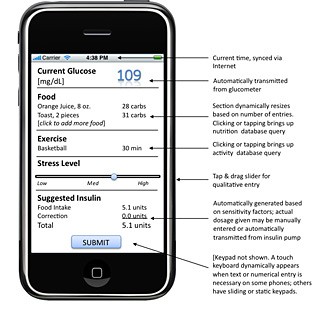

Here’s how Hannemann’s system works: You check your blood sugar level using a glucometer, which automatically and securely transmits the reading to a smartphone and, simultaneously, to a Web-based patient record database, where it’s stored. On the smartphone, a special application has popped up prompting you to record information about your latest meal or recent physical activity. As you enter those values, you are assisted by the application’s ability to search the Web for nutrition information. This simplifies the entry process, Hannemann says, and thereby encourages improved data acquisition.

The mock-up from Hannemann and Eisinger’s white paper shows what a sample readout from the integrated diabetes management system might look like on an iPhone. The application would work on other smartphones as well. (Photo by Chris Hannemann.)

Based on all the input, the application instantly provides a recommended insulin dosage. You receive an automatic injection from your insulin pump, and the device wirelessly transmits that data to your smartphone and database. The system records everything in a digital diary, so you no longer have to write everything down or make a mental note to record it later. Using either the smartphone or laptop, you then access your password-protected patient record database. A customized application crunches the numbers and presents glucose level trends, cause-and-effect relationships and allows you to query your records for more in-depth analysis. When you next visit the doctor, he or she can log onto the database, review the record with you and adjust treatment accordingly.

Judges saw the project’s potential when they awarded Hannemann and his teammate Sarah Beth Eisinger (B.S.’07 EECS) second place and $7,000 in the CITRIS-sponsored “IT for Society White Paper Competition,” part of the 2007 Bears Breaking Boundaries Contest. The award-winning white paper describes in detail how Hannemann’s system improves on existing methods of record-keeping such as paper diaries, glucometer/insulin pump memories, desktop management software and other computerized systems.

“There’s nothing particularly novel about the technology,” Hannemann says. “It’s just a matter of integrating a bunch of existing technologies to work together seamlessly.” He got the idea for the system after a serious hypoglycemic event, which resulted in a concussion and a disorienting visit to the hospital. The experience, he says, woke him up to the reality that he was managing his diabetes too casually. He began logging his intake and activity data on Google Docs, which impressed his new endocrinologist and led him back to colleague Eisinger (with whom he had attended high school years earlier in northern Virginia), who by this time was working at Google.

Now working full time at eSolar in Pasadena, California, Hannemann finds he doesn’t have as much time as he would like to bring his device to fruition. He’s about halfway between concept and prototype, he says, and is cultivating relationships with a medical group focused on diabetes treatment as well as product engineers from what he describes as one of the leading vendors of medical diabetes technology.

For more, see the white paper, Integrated Diabetes Management, or e-mail Hannemann at IntegratedDiabetes@gmail.com.