Making Art Out of Earthquakes

Berkeley's Ken Goldberg explores how to help people understand the physical realities of a geologically active world.

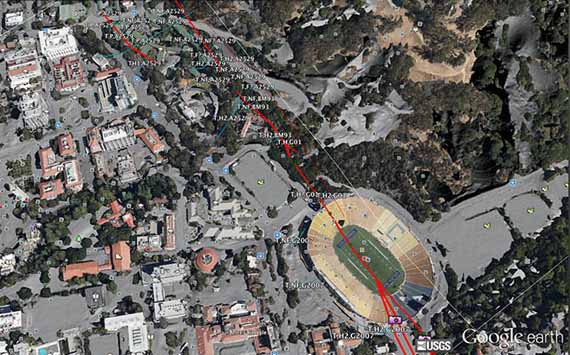

The Hayward Fault runs through the center of the UC Berkeley campus, famously splitting the university's football stadium in half from end to end. It has, according to the 2008 Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast, a thirty-one percent probability of rupturing in a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake within the next thirty years, making it the likeliest site for the next big California quake.

Nonetheless, for the majority of East Bay residents, the fault is out of sight and out of mind--for example, five out of six Californian homeowners have no earthquake insurance.

The Hayward Fault trace superimposed onto a map of the University of California, Berkeley, campus, as seen in the USGS Hayward Fault Virtual Tour

Meanwhile, three-quarters of a mile north of Memorial Stadium, and just a few hundred yards west of the fault trace, is the office of Ken Goldberg, Professor of Industrial Engineering and Operations Research at Berkeley.

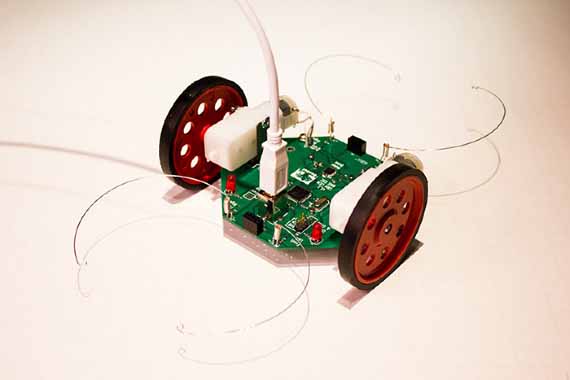

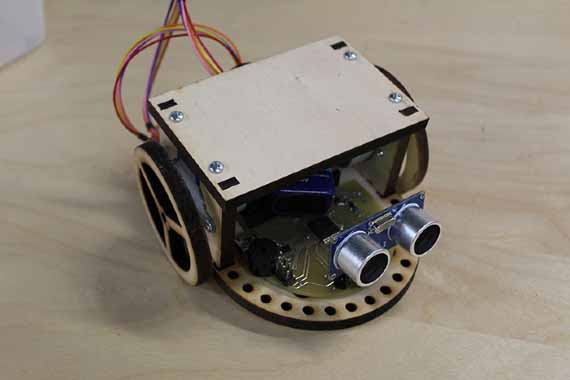

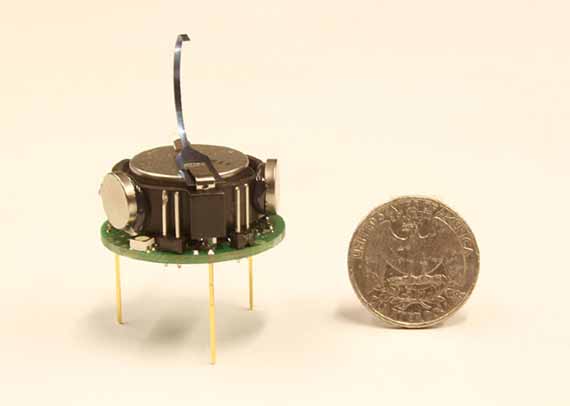

Goldberg's extensive list of current projects includes an NIH-funded research initiative into 3D motion planning to help steer flexible needles through soft tissue and the African Robotics Network, which he launched in 2012 with a Ten-Dollar Robot design challenge.

Three robots from the "10 Dollar Robot" Design Challenge organized by the African Robotics Network

Alongside developing new algorithms for robotic automation and robot-human collaboration, Goldberg is also a practicing artist whose most recent work, Bloom, is "an Internet-based earthwork" that aims to make the low-level, day-to-day shifts and grumbles of the Hayward Fault visible as a dynamic, aesthetic force.

Screenshot of Bloom, 2013, by Ken Goldberg, Sanjay Krishnan, Fernanda Viégas, and Martin Wattenberg

Venue stopped by Goldberg's office to speak with him about Bloom and the challenge of translating invisible seismic forces into immersive artworks.

Our conversation ranged from color-field art and improvisational ballet to the Internet's value as a vehicle for re-imagining the relationship between sensing and physical reality. The edited transcript appears below.

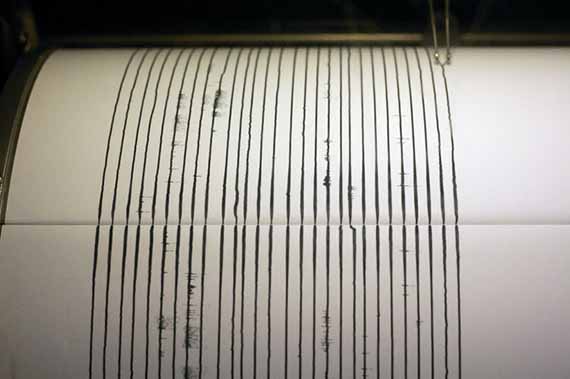

A Bay Area seismograph (Marcin Wichary)

Nicola Twilley: When did you start working with seismic readings in an artistic context, and why?

Ken Goldberg: Well, I had just finished grad school, I had started teaching at USC in the Computer Science department, and I was doing art installations on the side. And I was building robots.

I had just completed an installation for the university museum when I stumbled onto this, at the time, brand new thing called the World Wide Web. My students showed me this thing and I realized: this is the answer! The Web meant that I didn't have to schlep a whole bunch of stuff to a museum and fight with all their constraints and make something that, in the end, only 150 people would actually get out to see. Instead, I could put something together in my lab and make it accessible to the world. That's why we--I worked with a team--started developing web-based installations.

The Telegarden, 1995-2004, networked art installation at Ars Electronica Museum, Austria. Co-directors: Ken Goldberg and Joseph Santarromana Project team: George Bekey, Steven Gentner, Rosemary Morris Carl Sutter, Jeff Wiegley, Erich Berger. (Robert Wedemeyer)

We actually built the first robot on the Internet, as an art installation. It got a lot of attention--tens of thousands of people were coming to that. Then we did a second version called The Telegarden, which is still the project I'm probably best known for. It was a garden that anyone online could plant and water and tend, using an industrial robotic arm, and it was online for nine years. I actually just found out that there's a band called Robots in the Garden, which is exciting.

What was really interesting to me about The Telegarden was this idea of connecting the physical world, the natural world, and the social world through the Internet. I was interested in the questions that come up when the Internet gives you access not just to JSTOR libraries and to digital information, but also to things that are live and dynamic and organic in some way.

That really drove my thinking, and my colleagues and I began to do a lot of research in that area. I registered some patents and won a couple of National Science Foundation awards, formed something called the Technical Committee on Networked Robots, and wrote a lot of papers. From the research side of it, there are a lot of interesting questions, but, from the art side, it also led to a series of projects that look at how such systems were being perceived, and how they were shaping perception.

I worked with Hubert Dreyfus on a philosophical issue that we call "telepistemology," which is the question of: what is knowledge? What counts as objective distance? In other words, people were interacting with this garden remotely, and that raised the question of whether or not, and how, the garden was real, which is the fundamental question of epistemology.

The Telegarden, 1995-2004, networked art installation at Ars Electronica Museum, Austria. Co-directors: Ken Goldberg and Joseph Santarromana Project team: George Bekey, Steven Gentner, Rosemary Morris Carl Sutter, Jeff Wiegley, Erich Berger. (Robert Wedemeyer)

Epistemology has always been affected by technologies like the telescope and the microscope, things that have created a radical shift in how we sense physical reality. As we started thinking about this more, we became interested in how the Internet is causing an analogous shift, in terms of, hopefully, reinvigorating skepticism about what is real and what is an artifact of the viewing process. I edited a book on this for MIT Press that came out in 2000.

In the middle of all that, then, I moved here and met someone from the seismology group. They agreed to give me access to this live data feed of movements on the Hayward Fault, a tectonic fault that cuts right through the center of Berkeley--in fact, right through the middle of campus, not far from here. I was really interested in this idea of connecting to something that was not just the contained environment of a garden, but something much more dynamic and naturally rooted and global.

I guess I should add, as well, that a big factor for me was when I moved up here and became intrigued by the total amnesia and denial that people here have about their seismic situation. I would ask people, "What do you have in your earthquake kit?" And they would reply, "What? What are you talking about?" Now, of course, twenty years later, I don't have an earthquake kit, either. [laughs]

Manaugh: I think that's quite a common scenario. When we first moved out to California, we bought several gallons of water, a few boxes of Clif Bars, extra flashlights, and even earthquake insurance, and the native Californians I knew here just looked at us like we were paranoid survivalists, hoarding ammunition for Doomsday.

Goldberg: It was that sort of reaction that got me thinking a lot about how people are not conscious of the fault, or about earthquakes, in general, and I began wondering how you could make that more visually present. Also, the old seismograph was an interesting visual metaphor for me. Everyone recognized that form, but I wanted to play with it. I thought we could make a live, web-based version, which you can actually still see online.

Twilley: What form did that take?

Goldberg: The very first version was just a simple trace across a black screen. It was called Memento Mori and it was meant to be super-minimalist. In fact, when I showed it to the seismologists, they said, "Oh, where's the grid? How can we quantify this without a scale?" I had to say, no, no, it's not about that. We're just showing a sense of this--a visible signal. We actually wanted people to make an analogy with a heart monitor.

Screenshots from Memento Mori, 1997-ongoing, Internet-based earthwork (Ken Goldberg in collaboration with Woj Matuskik and David Nachum)

What's also interesting is that the trace mutates quite a bit. You come in at different times of the day and the signal is very different. It's sort of like the weather. The fault has different moods. When there is an earthquake, people will see big swings of activity with rings, because it goes on for days and days afterward. In fact, when there's a big earthquake in Turkey, you can pick it up here. It strikes the earth and then a signal comes around at the speed of sound, and then it goes all the way around again, and you get these echoes for weeks. Very small echoes can go on for months. And, every time there is a tremor, we get a huge spike in traffic.

I also liked the idea of making a long form artwork, like Walter De Maria's Earth Room, online.

The New York Earth Room, 1977, Walter De Maria. Long-term installation at 141 Wooster Street, New York City. (C4 Gallery).

Manaugh: Like a seismic Long-Player?

Goldberg: Exactly.

Part of this, I think, is that as an engineer, I'm really intrigued by the challenge of how you make the system stay on. A lot of times we have robotic projects, but they work once or twice, and then that's it. I feel like that's deceiving, because people may see them, or watch a video, and then they take away a certain sense of what robotics is. You have to be careful, because it sets false expectations. The kind of robotics in which you really build a system that can stay online and also take the kind of abuse that happens over the Internet is quite a challenge. I'm very big on this issue of reliability and robustness.

In any case, we put the Memento Mori system online and, after a year or two, Randall Packer, a composer here, approached me and said, "What about adding an auditory component?"

The actual signal frequency is too low--it's inaudible. If you just attach a speaker to it, nothing comes out. What you want to do is use it to trigger sounds, so that, essentially, the signal becomes like a conductor's baton, triggering this orchestra of sounds. Through that process of sonification, you can create a very auditory experience that's still driven by the seismic signal.

Twilley: So you could be using the signal to trigger a laugh track if you wanted to?

Goldberg: Exactly--the sounds don't have to be notes. Packer did it with a lot of natural sounds, like waterfalls and lightning and thunder--things like that--so it was very earthly. But by no means does it have to be musical. In fact, that's where we are now with Bloom, which is my most recent project.

We renamed the new auditory version Mori. We got a commission to do a project in Tokyo, at the ICC. They actually gave us a good amount of funding, so we ramped up and built this whole seismic installation with an acoustic chamber that was about fifteen feet square and had extremely powerful subwoofers underneath the plywood floor. The whole idea was that you could walk in and you could lie on the floor. We amplified the signal a lot, and there was this real sense of immersion, like you were essentially inside the earth. What was important is that it was live. Obviously, you could do this prerecorded, but it was essential to us that this signal was coming directly from the earth in real-time.

That was started in 1999, and, as it traveled around Japan and then to the The Kitchen in New York, we got closer and closer to the one-hundredth anniversary of the 1906 earthquake. I got this idea that I wanted to do a performative version. I wanted to do it in a very big space where everybody could experience it together at the time of the one-hundredth anniversary.

About a year before the anniversary, by chance, I was seated at a table next to a dancer--actually, the dancer--from the ballet. She was the principal dancer at the San Francisco Ballet--Muriel Maffre. After a couple of drinks, I got the courage up to ask her, "Would you ever consider dancing to the sound of the earth?" Amazingly, she said yes.

So Muriel, who is just an astounding artist and performer, took this on as a project. The idea was quite radical--that she would take a live seismic signal and respond to it on stage. And it's improv, because you don't know what's going to happen. We worked together for about a year, and we convinced the ballet to actually perform it in the opera house. It was about a week before the actual anniversary, in the end. She performed it on stage and it was about three minutes long. She did a phenomenal job. It was just a beautiful thing.

Twilley: How did you connect the signal to her, on stage?

Goldberg: We connected to the signal via the Internet, and we did the sonification right there on site, feeding it into their speaker system. She was just responding to the sound on stage.

What's so interesting about how the ballet works is that they do all these rehearsals and, then, when they actually set up for the performance, it all has to be done that same afternoon. There's no advance set up, because the space is in so much demand. You only have a few hours to get the whole thing tuned.

In this case, we were really cranking it--telling them to just turn up the volume. It was amazing to watch this old opera house, which actually was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and then rebuilt, start to vibrate. That was actually a big concern--were light fittings and so on going to fall?

Ruins of City Hall and the Majestic Theater in San Francisco, following the 1906 earthquake.

Manaugh: That reminds me of the artist Mark Bain, who actually got permission to install a massive acoustic set-up in a condemned building in the Netherlands; it got so loud, and the bass frequencies he was using were so extreme, that the building risked collapse--which, of course, was the entire point of Bain's performance--but the organizers had to shut it down.

Goldberg: The facilities guys actually said to me, "We don't want to drop the chandelier on people's heads! What if there's a spike in the earth's motion that would cause the sound levels to blow up?" I don't know if that's even feasible, but we put a clip on it so, if there was a sudden event, the system wouldn't be overwhelmed.

From there, I went on to do a limited series of the original Memento Mori piece that collectors could purchase. There was an artist's edition that would always be publicly available, but people who bought their own edition got their own version that they could label, and that included some private data. But, in the course of developing that, I started thinking, why does it have to be so grim? When I originally conceived it, I was really into the minimalist aesthetic. It was just black and white and about mortality. But I started thinking: why? It started seeming very dark.

So I started thinking about what else this signal could be used to generate, something that would be more visually stimulating and more engaging. That's what gave rise to my new project, Bloom. Bloom is meant, in some sense, to invoke something that's more natural and organic. It still references mortality, but in a much more positive way. Maybe it's because I'm getting a little older or something like that!

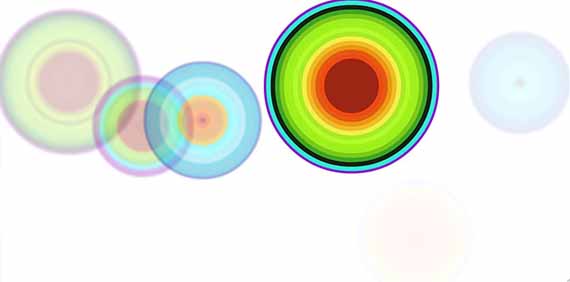

Screenshot of Bloom, 2013, by Ken Goldberg, Sanjay Krishnan, Fernanda Viégas, and Martin Wattenberg.

Bloom is basically the idea that all flesh is grass, and that we can look at natural plant growth and organic material as outgrowths of the Earth. The seismic signal is a representation and reminder of this organic substrate, so I thought: let's use it to trigger the growth of forms. I'm just going to play it for you. [launches beta version of Bloom]

Manaugh: What are we actually seeing right now? What scale of seismic activity do these blooms represent?

Goldberg: What you're seeing right now is just normal variation. For example, when a big truck goes up Hearst Avenue, which is not far from the seismometer, there's a signal from that. And then, at any given time, there are actually lots of tremors going on around the world, so you're picking up all the echoes of those. It's actually really rich to try to do signal-processing in order to extract signals from the noise, because there are also resonant elements from, for example, the beating of the surf on the California coast.

There's actually a huge amount of information coming through here. What's interesting is that this display is so different to what earth scientists are used to looking at. They study plots and seismographs, and so on. We're actually going to have a meeting with them to talk about their perceptions of this and how they respond to it. My sense is that they probably won't find it that valuable, because there's no real scientific benefit to it--although it would be interesting to see if someone who really understands the signal could look at this thing for a while and actually start to read it.

For us, it's really more of an abstraction.

Twilley: Can you explain how the blooms' particular colors and forms are generated?

Goldberg: The blooms are triggered from left to right, so there's still this idea of temporal progression, and they are triggered depending on whether the signal is switching. The relative size of each bloom is generated by the size of the signal change. The color choices come from a feed from Flickr--a search for flower images to pull up a data set that we can use to source the color variations.

I'm working with these two wonderful data visualization folks, Martin Wattenberg and Fernanda Viégas. They are amazing: Martin has a Math PhD from Berkeley and went off to work at IBM. He's done a huge number of these visualizations for data of all kinds--most famously, for baby name data. All of his interfaces are just fantastic and we've been friends for a long time. He then started working with someone I knew from MIT, Fernanda, who is a painter by training. The two of them started to do all these amazing projects with IBM, and they had their own lab, which they eventually took private. Then they got bought by Google, but Google seems to give them pretty free rein to do whatever they want. We started working on this about a year ago.

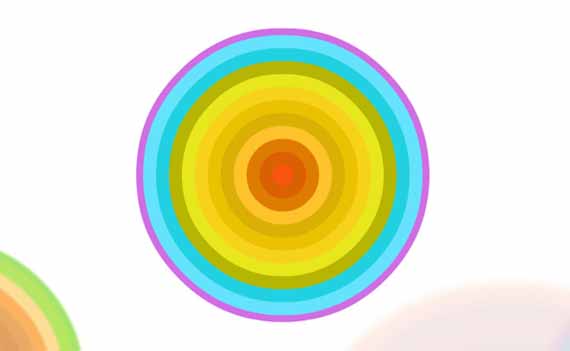

I should also explain the reference to Kenneth Noland. I'll confess to you--I didn't really know his work when I began this project. I gave a talk to some art historians, and they said, "Oh, it's so nice that you're referencing Kenneth Noland in this way!" I was like, "Who?" They were a little horrified. [laughter]

Noland was a New York color-field painter, whose work is a lot like what we had started generating with Bloom--so I dedicated the project to him. We wanted to play with that reference. What's amazing is that he passed away just a year ago.

Screenshot of Bloom, 2013, by Ken Goldberg, Sanjay Krishnan, Fernanda Viégas, and Martin Wattenberg.

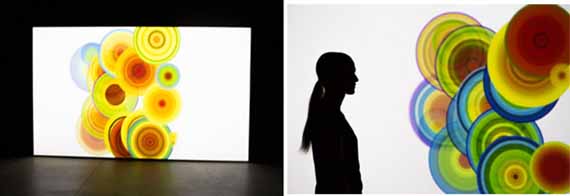

In any case, we're still fine-tuning things, including the fades and the way that the colors are derived from the data and how it's going to be installed in the gallery and so on. The experience in the museum is always more immersive and hopefully more dramatic than it is online. The ideal situation for me is that you would come in on a kind of balcony and you could look down twenty or thirty feet and see all of the colors blooming there below you.

Bloom installed at the Nevada Museum of Art

Bloom is currently on display at the Nevada Museum of Art, Venue's parent institution, through June 16, 2013.

This post was originally published at V-e-n-u-e.com, an Atlantic partner site.

This post was originally published at V-e-n-u-e.com, an Atlantic partner site.